Let’s have a look at the typical products available in the Montreal area.

Asphalt shingles in all their various forms, constitute anywhere from 50% to 95% of the installed roofs (for sloped residential roofs) with the proportion depending on the area of the city or region. They are the cheapest form of roofing, are readily available from any number of sources, and are the easiest to install. They also are not waterproof, can easily blow off (if not properly installed), and usually last from 10-15 years. The exact kind of weakness they show depend on the type and brand of shingle, but in general, even with good installation practice and proper preparation, they usually don’t last much beyond 18 years.

Tar and gravel roofs are quite common in certain areas of the city, and are found on flat and lower sloped (2:12 to 3:12) roofs. They were very inexpensive to install, and generally last 20-30 years. However, given that they are “built-up roofing” made from successive layers of tar paper embedded in roofing tar, they depend on good installation practice both in the laying down of the basic material, and in the flashing details at the roof perimeter and any penetrations. At this time, the number of companies that continue to do this work is much less than before, and they tend to be large commercial outfits.

Membrane roofs are now seen more and more, replacing the tar and gravel coverings on low-slope roofs. These membranes are of different construction and use different materials, but the most common is a form of modified asphalt sheet (usually two-ply), that is installed in overlapping layers. There are different installation methods, with some being glued down, and others requiring open flames to melt and seal the layers. The latter is called “torch-on” membrane, and should be installed only by insured craftsmen. Durability and effectiveness depends very much on the installation skill and detailing, but a well-installed membrane roof should last about 20-25 years.

Metal roofs were very common in our region before asphalt shingles became the common material, partly because of our snow loads – they allowed the snow to slide off and reduce the load on the roof. Since those times, metal roofs evolved in a dramatic fashion, creating products such as standing seam roofs, steel, aluminum and copper shingles, various profiles of metal panels that resemble clay tile, or wood shake, or architectural asphalt shingles. The roofs range from very cheap (generally thin screw-through panels) to very expensive (hand-made copper or stainless steel coverings). Most metal roofs come with 50-year (give or take) product warranties, and if properly installed, can be expected to last over 100 years. On the other hand, the choice of which metal product is most appropriate for a given situation is something that many homeowners just don’t have the knowledge to make, and are very susceptible to the salesperson pitch. Proper installation also plays a very important role in the actual longevity of the products, and this is also an area where most people just don’t have the experience to ask the right questions.

Wood or cedar shingles used to be very common roofing materials, but with the disappearance of first-growth cedar, the prices have skyrocketed, and these products are available usually only on high-end homes. Being a natural product, they have a unique appearance, but also require a certain amount of maintenance and care to reach their potential life. They have to be installed in a manner that allows them to shed water and to drain well, so that there is little chance of trapped water promoting rot. Installing these is a very skilled trade, and there are only a few contractors in our region that do a proper job.

Slate is a relatively common material for roofing, especially in areas like Westmount and Outremont. It is a beautiful, historic covering, and properly installed will last well over 100 years. However, both the material, and the skilled labour needed to install these is quite expensive, so these are now found only on high-end homes that can handle the weight, and whose homeowners can afford to pay for the maintenance.

Clay tile (and its cousin, concrete tile), is a very common material in many parts of the world, and is found also in our region. However, in addition to the weight, our frequent freeze-thaw cycles wreak havoc on any tile that has a crack forming on it. In addition, most homes are not designed to hold up the amount of static weight that such a roof will represent. Maintenance is also an issue, since these are relatively fragile, and should not be walked on. We find that homeowners often choose to replace these with metal products that have a similar appearance, without the fragility of true clay.

There are newer materials coming onto the market, including fake slate made from recycled plastic and rubber, and fiberglass panels. Time will tell whether their initial attractiveness will last or whether the UV exposure and temperature extremes will cause damage. Earlier versions of these products came onto the market and were withdrawn after frequent failure. Maybe the new generation will finally get the mix right.

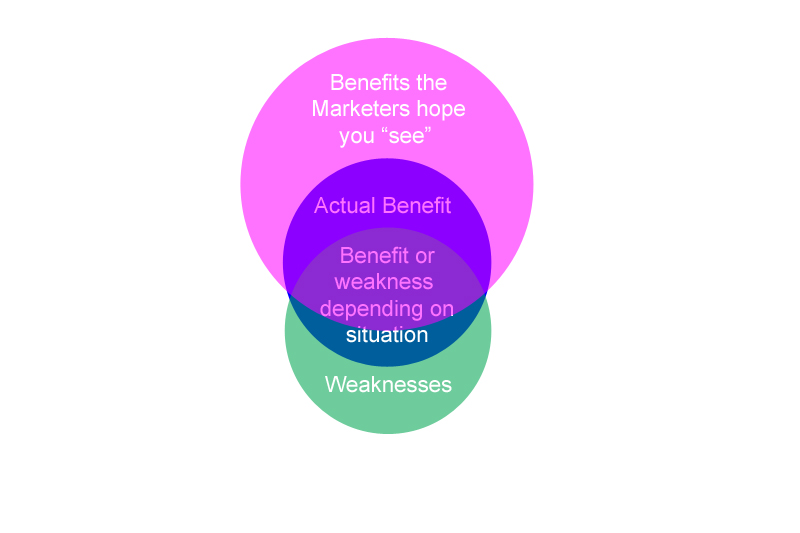

One important consideration in choosing a roofing material, is the life-cycle cost. What IS the actual duration of the “trouble-free” period for each type of material (and the method of installation)? Since failure usually starts at the weakest part of the system, it is important to know what that part is, and to do the required maintenance so that part can last as long as the rest of the roof system.

An example of the type of problems that can occur is an asphalt shingle installation over an OSB (Exposure Type 1) deck. Even when properly installed, some shingles will start letting in water (via the nail holes) in as little as eight years. Once that water starts entering the OSB decking, the glue starts to deteriorate, and the OSB panel starts losing strength and integrity. The shingles may still look good on surface inspection, but the seepage pattern visible from the attic will tell otherwise.

A very common waterproofing technique is to use caulking in “waterproofing” various roof joints and penetrations. The more common caulking formulations lose their resiliency and adhesion in as little as five years, even when properly installed. Is it a coincidence that most installation warranties (on asphalt shingles) only last 5 years? The way around this is to build the roof system so that the caulking is more or less cosmetic, with the real waterproofing happening behind/below the caulking. Ah, but THAT takes more expensive materials, and more labour to install, and besides, it can’t be seen, so why bother? This detail work is the difference between a waterproofing joint that will last 5 years (more or less) compared to a waterproofed joint that will last 20-30 years or more.

Therefore, when looking at the life-cycle cost, it is important to consider both the material AND the way the product is installed. Certain materials (like asphalt shingles) are more susceptible to other deficiencies in the roofing system, like improper insulation and/or ventilation. In addition to “pure” life-cycle costs of the roofing system only, you also need to consider the costs associated with the risks of failure. For example, if the roofing system fails gradually over time, and there is persistent low-level leakage into the roof decking, then this may be a minor issue if the decking is solid wood, but may be a major issue if the decking is OSB( exposure Type 1). If the house in question also has ice damming issues (due to insufficient insulation and ventilation), then it is almost guaranteed that there will be serious roofing issues and damage UNLESS the proper preparation and waterproofing was done.

Therefore, in order to make an intelligent purchasing decision when choosing among the various roofing materials available, it is important to also understand the current weakness of YOUR specific roof to know what preparation, waterproofing, and additional work such as ventilation and insulation improvement is needed in order to achieve the promise of what the roofing system could deliver. Since changing a roof is a major expense for most people, shouldn’t you know that you’re getting the best product and installation for the money you will need to invest?

If you’re not sure about the best fit for your situation, contact me. We’ll examine your current situation, determine which factors we need to take into account, and review the options you have. Now you will be in the best position of knowing what needs to be done and how it should be done, without worrying about whether short-cuts have been taken. No point in wasting your hard-earned money, and putting your most important investment at risk!

(c) 2014 Paul Grizenko